Jai Subedi, 38, meticulously counts the inventory in his small store ensconced in the north of Syracuse, New York.

RELATED:

Europe Closes Borders for Refugees, Latin America Opens Doors

He pauses then rubs the palms of his hands and, securing his muffler, steps out to help two men unload towering crates of water bottles, along with sacks of onions, and apple cartons, from a truck stationed outside.

It's February 2014.

Before Subedi moved to Syracuse in upstate New York nearly nine years ago through the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) program, he had spent nearly 18 years at the Sanischare refugee camp in Nepal, along with members of his family.

Subedi is one of tens of thousands who endured fierce political strife, living in shambles for nearly two decades. His face turns grim as he recalls his life in exile.

When I first met him, four years ago, he said he had no regrets but had lived a very hard life.

Subedi is a "Southerner" who belongs to the Lhotshampa community of Nepali ancestry. At least 80,000 Lhotshampa living in the south of the country were forced to leave in the early 1990s by the ruling monarchy as it enacted the single identity policy: "one nation, one people."

"It is a rural country between two giant countries (India and China), so no one really knows where Bhutan is," Subedi explained to me in a recent conversation.

"Hundred of years ago, our people – our forefathers – were taken away from Nepal to build Bhutan, to develop its infrastructure such as roads, bridges, etc, so as southern Bhutanese, we are ethnically Nepalese

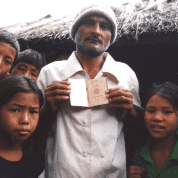

Jai Subedi with his family at his home in Syracuse, New York. | Photo: Jai Subedi

"We are very hardworking people: our people started owning farms and other lands, reaching high governmental positions. The ruler – the monarchy – didn't feel comfortable with our progress.

"Since we are a minority, when the government brought the 'one nation, one people' policy, my father, my uncle and other members of the family suffered human rights violations.

"The government started putting (Southern) people in jail; they were tortured, started forcing people to leave the country."

Subedi was 12 years old at the time. "They put out a notice for us to leave the country in 13 days. My father was called to a government building to sign a document which said that we were leaving our lands voluntarily to the government; we just fled with nothing. That's how we landed at the Nepal border, later living in camps in Nepal."

Bill Frelick, refugee program director at Human Rights Watch, said in a statement: "In the late 1980s, Bhutanese elites regarded a growing ethnic Nepali population as a demographic and cultural threat.

"The government enacted discriminatory citizenship laws directed against ethnic Nepalis that stripped about one-sixth of the population of their citizenship and paved the way for their expulsion."

Bhutan: Not So Shangri-La

Bhutan, a Buddhist kingdom nestled in the mystic Himalayas, is also the birthplace of the Gross National Happiness (GNH) index.

In 1972, the fourth king of Bhutan, Jigme Singye Wangchuck, coined the term for a more "holistic" approach to measuring the country's prosperity, based on the wellbeing of its citizens.

But it was Wangchuck who was responsible for the mass exodus of the Lhotshampas, roughly one-sixth of Bhutan's population.

"Bhutan ousted its own citizens, but claims to follow the Gross National Happiness!" said Subedi. "I hate it when Bhutan talks about Gross National Happiness; it's a facade."

Bhutan measures progress and achievements based on categories such as psychological well-being, health, time use, education, culture, good governance, community vitality, ecology and living standards, but some find the parameters redundant.

Namgay Zam, 32, hosts a radio show on mental-health challenges among the Bhutanese. Zam believes the idea of GNH has been hijacked by the West and turned into something it was never intended to be, according to a report by NPR.

The concept of GNH is based on the principles of Buddhism and tenets of compassion, contentment and calmness. "You don't quantify Buddhism," Zam told NPR.

Needrup Zangpo, executive director of the Journalists' Association of Bhutan, told NPR: "The outside world glamorizes Bhutan, but overlooks a list of problems besetting the country."

In 2016, youth unemployment stood at 13.2 percent, up from 10.7 percent the previous year, according to government data reported by national newspaper Kuensel. "We have an increasing income gap, we have increasing youth unemployment, environmental degradation," Zangpo said.

In 2016, Bhutan's Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was nearly US$2.2 billion, according to the World Bank, and the nation remains on the United Nations' list of "least developed countries."

With melting glaciers, climate change and failing hydropower plants, a major source of the country's energy and revenue, as Zangpo points out, "We have a lot of things to worry about."

Critics say the issue started when King Wangchuck introduced the Bhutanese Citizenship Acts of 1958 and 1985 to remove Lhotshampas from the country.

The act, which required proof of 15-year legal residence from citizens in order to obtain a certificate of nationality, had several other restrictions. Failure to provide the necessary documents meant applicants would be deemed "illegal residents."

Human rights groups report that even those who could supply the required proof were often evicted, according to The Diplomat.

On June 10, 1985, using the citizenship act as a premise, Wangchuck enforced a Nationality Law, known as the 'One Nation, One People' (ONOP) policy, through which he forced one-sixth of Nepalese-origin residents out of the country.

Hari Bengaley Adhikari, another Lhotshampa who settled in Syracuse, is the founder of the local Bhutanese community, which has swelled to nearly 3,000 members.

Adhikari used to own a footwear store in the Tsirang district in the Southern part of Bhutan. Things went awry when the government started implementing the ONOP policy in 1988, he said.

Adhikari was arrested seven times by Bhutanese police for leading peaceful protests against government atrocities carried out against the Lhotshampas. "Once, I was locked in the district office toilet for almost 36 hours," he recollects.

Upon his final release, Adhikari was told by a police guard: "The king has been kind enough to offer amnesty to you. You have been in custody several times. If you continue this way and involve yourself in activities against the king, we won't spare you."

Adhikari told me: "It was not a pleasant place to live, but we believed that this kind of a situation will not last for long and we will return back to our homes.

"We wanted to lobby with the Indian government and human rights groups and other sources who could have influenced the government to change their stance."

After being deported from Bhutan, Adhikari lived in Beldangi Camp II in Nepal, where he volunteered as a camp secretary.

"It was hard: there was no light, no electricity and water supply was also short. We used to burn charcoal that has a serious effect on health.

"The money provided was not enough to support the family, so we had to work outside the camps and borrow money from relatives outside of the camp.

"The refugees provided the cheapest labor in the area, as they were restricted to work outside the camp but had to make ends meet."

Life After Limbo

In March 2008, Adhikari arrived with his family in Syracuse, where they were housed in an apartment in the north. "It was so cold. There was so much snow. We couldn't go out. There was no one to interact with.

"Initial days were hard, as we couldn't survive on the vegetables that were sold at the grocery stores nearby. We couldn't even find appropriate tea leaves: green tea was too mild for our taste."

After a couple of weeks, Adhikari began visiting the resettlement office on an almost daily basis. "They gave me computer access and I could check my emails."

The U.S. Department of State's Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) manages the Refugee Admissions Program (RAP).

In 2012 alone, 58,238 refugees were admitted under RAP from 56 countries. Bhutan and Myanmar constituted more than half of the refugee population.

From Bhutan, 15,070 refugees (25.88 percent) came to resettle in the United States. Burmese refugees came a close second with 14,160 refugees (24.31 percent), while 12,163 Iraqi refugees (20.88 percent) made up the third-largest refugee population.

New York State has the fourth-largest population of resettled refugees in the United States.

Refugees who are twice displaced – first from their own country then after years spent in limbo at resettlement camps – often find it hard to readjust themselves to new surroundings.

According to a 2012 report by the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP), between February 2009 and 2012 the suicide rate among Bhutanese refugees was 20.3 per 100,000 people. That's double the rate in the general population in the United States, and exceeds the global suicide rate of 16 per 100,000, according to figures from the World Health Organization.

"Different psychological stressors occur at each stage of the resettlement process," the CDCP report notes. Leading factors include psychological trauma undergone in refugee camps; post-migration difficulties, and lack of familial ties.

According to Adhikari, there are multiple factors that leave refugees feeling alienated and removed from their new surroundings: third-country resettlement is not always a favorable "long-term" solution.

"Educated families can begin to stand on their feet, while families having uneducated members suffer as they are unable to integrate themselves with the changes in their environment.

"There are not many training opportunities to help land a job, generate income and become self-sufficient according to their skillset. People who are well educated, like doctors and engineers, go for cleaning jobs and other types of manual work here."

According to the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), the Voluntary Agencies Matching Grant Program is an alternative to public cash assistance, providing services to help eligible refugees become economically self-sufficient within 120 to 180 days of program eligibility.

Adhikari, however, says "the time frame for which the refugees are supported is not sufficient."

Living in a new community also brings challenges. "There are children from the local community that pelt stones on us," Adhikari says. "Police are helpless and cannot take action against them as they are juvenile."

There have been several incidents of physical assault, often targeting those most vulnerable in the community. Some assaults are motivated by theft; others are motivated purely by hate.

"The local police are very cooperative: they act swiftly upon such incidents, but sometimes it is hard to find the culprits," says Adhikari. "This is what we call 'home' now."

When I met Subedi again in March of 2014, he sat with a small coterie of fellow Bhutanese. It was just before Bhutanese Community Day, an annual celebration marking the first Bhutanese family's settlement in Syracuse.

Subedi became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 2013, shortly after being made redundant from his job as a caseworker with Interfaith Works, a faith-based resettlement agency in Syracuse.

"When the refugees' flow was totally reduced in 2017, I was laid off for two months. I was working part-time jobs, but was hired back full time and worked until December and then got laid off again."

Since U.S. President Donald Trump came to power, the number of refugees coming to the region has dwindled. Trump has also cost jobs for many caseworkers, including himself.

"There are not many people coming in. I was at Interfaith works recently and the director showed me the numbers: 14 people came in December, six in January, in February, three people are in the pipeline, which in turn has also led to staff cuts.

"Sometimes we used to have 80 to 90 people come in a month's time, sometimes 107. On average, there would be at least 40 to 60 people."

Subedi now works for a regional for-profit home healthcare company, True Care Connections. "At least I still get to serve my community, since part of the job is we visit people at home," he said.

On March 24, the community will mark its tenth anniversary. "The event will have some of the same elements as you saw four years ago," Subedi told me.

In 2014, at a local school hall packed with nationalistic vigor, Subedi addressed more than 300 hundred people, including government officials, the chief of police and representatives from the Mayor's Office.

"It's important to show the local community the trajectory of events that lead to our exodus," Subedi said, referring to a presentation he's working on which depicts a brief history of their lives in Bhutan, their lives as refugees, and their transition to life in the United States.

Members of the Bhutanese community attending a gathering in Syracuse, New York. | Photo: Jai Subedi

During his 2014 speech, Subedi's voice was proud and hopeful as he addressed the audience, both young and old. "This journey from statelessness to uncertain future to 'hope' and 'aspirations' became a driving force for us to seek economic prosperity and neighborhood stabilization." Loud applause filled the hall.

"Nearly 300 families have become U.S. citizens and homeowners," Subedi told me recently, emphasizing how his community is prospering. "More and more of us are becoming homeowners; we are owning cars, properties. We are working hard."

For Subedi and many others who have spent a significant portion of their lives in refugee camps, owning a home is an important symbol; a landmark achievement. As he turns to go, Subedi says simply: "God bless us, God bless America."